Outdoor Advertising isn’t dead yet. But can it help solve a murder?

There are a few moments in the life of an advertising agent when our craft is hoisted to the forefront of society’s collective attention, and you can turn to your friends and say, “Yeah, that’s what I do.” And when advertising does make an appearance, it usually surfaces as narrative texture in a TV or movie plot. Done well, it’s the fulcrum around which a more complex plot pivots (Mad Men); at its worst, it’s the set-up for a two season reality show (The Pitch); and somewhere in between, it’s the leading man’s quirky job in an above-average romantic comedy (How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days). Never, however, has advertising’s role in narrative film been more ambitious than in Martin McDonagh’s dark comedy, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri.

The plot of Three Billboards revolves around a few key characters: Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand), the bereft and ornery mother of murdered daughter Angela; Sheriff Willoughby (Woody Harrelson), Ebbing’s affable and universally liked lawman; and Jason Dickson (Sam Rockwell), Willoughby’s degenerate and “vaguely racist” sidekick.

The movie wastes no time getting started, opening on Mildred Hayes taking out a year-long contract on three ancient billboards—are those bulletins or posters?—on a seldom-traveled side road outside the sleepy fictional town of Ebbing, Missouri. The billboards’ serialized message is simple: “Raped while dying, and still no arrests? How come, Sheriff Willoughby?” The billboards quickly come to the attention of local press and law enforcement, and Hayes is left to defend her ads at every turn. Ebbing isn’t a place that takes kindly to feather rufflers, and the billboards draw the ire of the locals en masse, including Sheriff Willoughby, Dickson, Hayes’ son’s classmates, and even the local priest. Hayes is relentless though, and the billboards remain despite what seems like all of Ebbing’s admonition to take them down. In over 120 minutes of running time, Hayes fights the law and small-town politics, refusing to let her daughter’s murder fade from Ebbing’s consciousness.

McDonagh touches on a few topical themes along the way, including racism and domestic/police violence, without fully diving into any of them. Plot turns in Three Billboards occur with the violent abruptness we’re used to seeing out of McDonagh, sometimes with fiery and arresting images juxtaposed before an operatic backdrop of sound. No one is purely good or purely evil in Three Billboards, and everyone is capable of redemption. A painful flashback midway through the film reminds the audience that Hayes is no perfect mother, making one wonder if her non-traditional media plan is as much penance for parenting regrets as it is about finding her daughter’s killer.

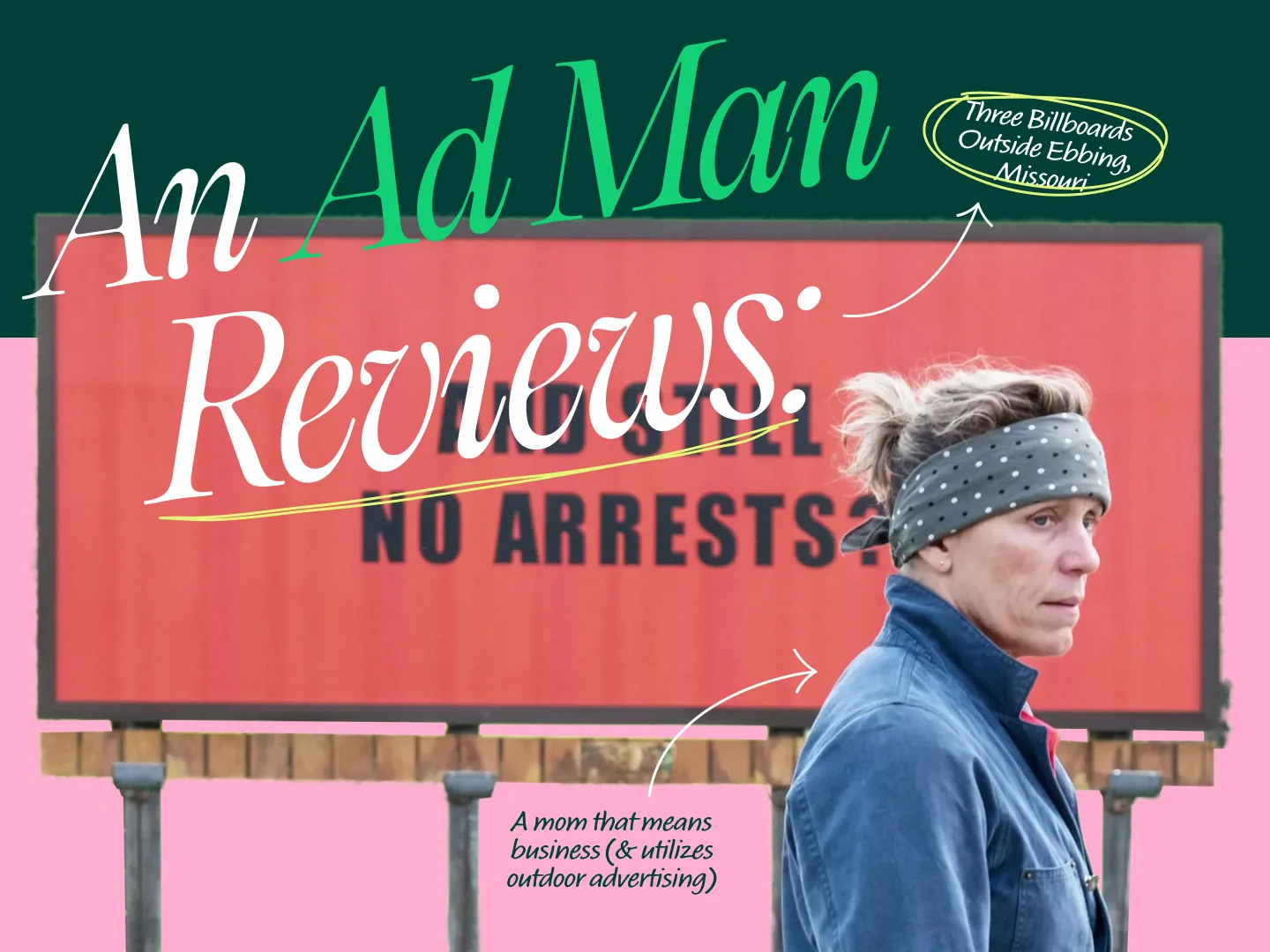

Frances McDormand plays Hayes with all the raw abrasion of a twilighting Nick Nolte, a far cry from her warm Oscar-winning portrayal of Marge Gunderson in Fargo. She curses, smokes, drinks, seldom smiles, and never apologizes. The utilitarian nature of her character is reinforced by her spartan appearance: no make up, blue mechanic suit, and at times, a crips-blue bandana fashioned around the perimeter of her head. Her quest to draw attention to, and ultimately find the killer of, her daughter escalates into a small-scale war—fire and all—with Ebbing as the theater.

Harrelson and Rockwell deliver layered and complex performances, worthy of admiration. A colorful supporting cast—including a humorous appearance by Peter Dinklage—rounds out a just-shy-of-authentic portrait of the rural American Midwest. There are a few questionable character choices, but overall, the cast’s effect is compelling.

Several lines of dialogue poignantly stood out, both from the perspective of an ad man (“When you can’t trust lawyers or advertising men, what has America come to, huh?”) and just as a human being (“Maybe I’ll see you again, if there’s another place. If there ain’t, well, it’s been heaven knowing you.”) On average, McDonagh’s signature screenwriting style drives the plot forward smoothly. Still, there are moments where the off-kilter, superfluous dialogue leans toward awkward rather than humorous, leaving one to wonder if something was lost in translation between McDonagh’s zany Irish/British humor and the American actors tasked with manifesting it.

As an advertising professional, there were a couple of head-scratchers: I found myself thinking, “Is that the font Impact on the billboards? And since when do outdoor companies print back-ups at no additional cost?” But as a Martin McDonagh fan, he’s created something arguably masterful that slots just behind his best (In Bruges) and miles ahead of his more forgettable (Seven Psychopaths). Mad men and perfectly happy people alike will find their thoughts lingering on the film’s nuanced characters, Main Street cinematography, and quirky dialogue long after the billboards finally come down.